CO2 Laser Edmonton: Skin Resurfacing for a Flawless Glow

CO2 Laser Skin Resurfacing at Albany Cosmetic and Laser Centre in Edmonton provides advanced rejuvenation to reveal smoother, healthier, and more youthful skin. Dr. Alhallak (Ph.D.) and Dr. Tomi (MD), are both internationally recognized authorities who published and authored the comprehensive research in cosmetic and laser field.

Real CO2 Laser Resurfacing Results in Edmonton

After just one CO2 laser session at Albany Cosmetic and Laser Centre, many clients experience noticeable improvements in skin texture, tone, and overall radiance. As your skin naturally boosts collagen production in the weeks and months following treatment, you’ll continue to see enhanced skin tightening, smoothing of fine lines, and rejuvenation.

Our advanced fractional CO2 laser resurfacing is expertly designed to target multiple skin concerns, delivering clearer, firmer, and more youthful-looking skin tailored specifically to your aesthetic goals.

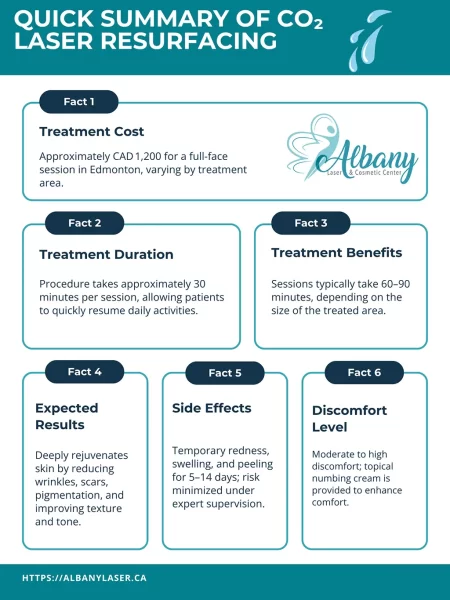

Co2 Laser Treatment Summary

Treatment Cost

Treatment Duration

Treatment Benefits

Expected Results

Downtime

Discomfort Level

Understanding CO2 Laser Resurfacing

CO2 laser resurfacing is a highly effective treatment that uses fractional carbon dioxide lasers to target deep layers of the skin, stimulating collagen production and significantly reducing wrinkles, scars, pigmentation, and other skin irregularities. This treatment is suitable for individuals experiencing advanced signs of aging, sun damage, acne scars, uneven skin tone, and texture issues. CO2 laser treatments are popular due to their transformative results and lasting improvements to overall skin quality.

Benefits of CO2 Laser Resurfacing

“Our advanced fractional CO2 laser not only rejuvenates the skin but targets deeper layers for lasting collagen production,” says Kamal Alhallak, Ph.D. This specialized approach ensures exceptional results tailored to your unique skincare goals.

- Noticeably smoother and tighter skin

- Enhanced collagen and elastin production

- Reduction of deep wrinkles and scars

- Improved skin texture and tone

- Renewed radiance and firmness

Preparing for CO2 Laser Resurfacing and Aftercare Timeline

3 to 7 Days Before – Preparation

- Avoid sun exposure and tanning to reduce the risk of hyperpigmentation.

- Discontinue retinol, exfoliating acids, and harsh skincare products.

- Stay hydrated and use a gentle, hydrating moisturizer.

Treatment Day – What to Expect

- Arrive with clean skin, free from makeup and lotions.

- A topical numbing cream is applied to minimize discomfort.

- The procedure takes about 30–120 minutes, depending on the area treated.

- Expect mild redness and warmth similar to a sunburn immediately after.

1 to 7 Days After – Immediate Aftercare

- Apply soothing creams and keep skin moisturized.

- Avoid direct sun exposure; use SPF 50+ sunscreen.

- Skin will peel and flake as it heals—do not pick at it.

7 to 14 Days – Ongoing Aftercare

- Redness starts to fade, and new skin becomes visible.

- Continue hydrating skincare routine with mild ingredients.

- Wear sunscreen daily to protect new skin.